The Making of Place

Cities have never been mere backdrops to human life. Their manners of design, growth and adaption have contributed significantly to the way we live. This, in turn, affects the strength of communities we form, the lifestyles we (are able to) adopt, our modes of living, working, commuting and being.

In the polis (city-state) of Ancient Greece, the need for public place was realised as early as the 5th century BC, where the agora and Pnyx were the central features of community life. The agora was a collection of temples and government buildings built around a marketplace, usually set at the higher hills of Mediterranian geography. The Pnyx was an amphitheatre, the spatiality of which enabled concentrated citizen-led debate. As ‘urban’ features, the two found relevance not only in their utilitarian purpose, but as common ground for social interaction, debate and the continuous unfolding of democracy.

The agora and pnyx in ancient Athens [The Athens Key]

“To ‘loiter’ here contained a positive connotation, for the place was rife with a plethora of civic engagement ...”

Aristotle brought to notice that cities were formed by synoikismos[1]–drawing together different families, cultures, identities, and economic interests. Normalising the awareness of difference in everyday urban environments forms the backbone of democracy, and continues to feature in contemporary urban design dialogue. The agora and pnyx enabled this by virtue of their spatial arrangements.

They were both large, open spaces situated along the main street of Athens. While the pnyx held focused performance (debate, theater, dance), a range of everyday activities would occur simultaneously in the agora.

To ‘loiter’ here contained a positive connotation, for the place was rife with a plethora of civic engagement – from public commerce, religious rituals, law and banking, to private parties and meetings. The spaces between activities were described by negligible barriers[1] – low walls and colonnades that proffered users the opportunity to intermingle, both visually and physically. Public and private realms were woven together in a manner that did not seek to compartmentalise. The city and the life it held were not at odds with each other.

This idyllic form has been severely challenged in the modern era, as cities grew exponentially in population, size and number. In 1950, there were only two megacities[10] - New York and Tokyo. By 2025, there are set to be more than thirty[2].

The challenges of designing modern cities lie equally in providing quality roads, sanitation, transportation, electricity, housing and economic opportunity, as in the manner in which these services are designed – both in relation to one another and the human users that seek them.

Left: Cities for cars [Putting People First]

“A reduction in the number and quality of meeting places also eroded the growth of local democracy.”

However, in most cases, the emphasis on ‘people-centric space’ reduced to make way for sprawled-out, ‘efficient’ cities. As suburban areas grew, distances from the city-centre increased and in cities where public transport was inadequately built, incentivised or both, the individual automobile became the preferred mode of interaction with the city. The car too, was more than a symbol of individual ownership; it was necessitated and justified by the way our cities have been designed. By focussing our cities on cars - objects that singularly take us from point A to point B - we look at the city as a place of collective destinations, rather than as a continuous journey[3] within a well-stitched urban fabric.

Cities became singularly important for their potential to bolster economic growth. Their capacity for creating healthy social habitats diminished, and with it, people’s ownership of their urban space ebbed away. A reduction in the number and quality of meeting places also eroded the growth of local democracy, as posited by historian Mary Ryan[4].

While economic growth and efficiency are undeniable pillars of development, a city, at its fundamental core, is comprised of living, breathing, thinking, and feeling people - people who are programmed to seek and form social connections. The social networks of a city are what last in times of need and difficulty. They contribute to building resilience by strengthening cultures and ties.

By the 1950s and 1960s, Western urbanists began turning to alternative solutions for cities, ones that placed human interaction as primary.

William H. Whyte, a sociologist and urbanist, recorded observations of people’s behaviour in public parks, plazas and other urban environments. Armed with a notebook, camera and research assistants, his work brought quotidian observations to the fore, which triggered thought and action on urban public space[5].

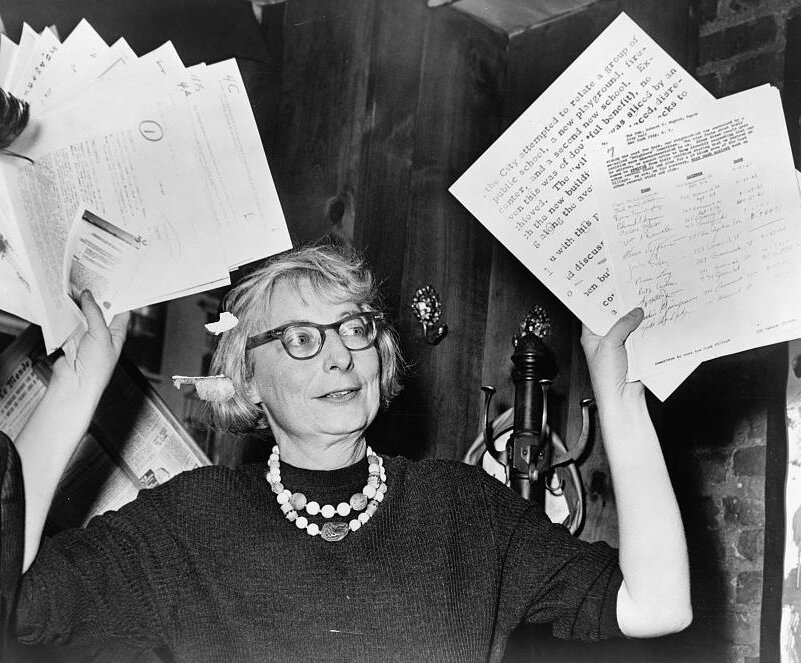

In 1958, Whyte recruited a young journalist for his written work on cities, who went on to write a seminal book on urban planning and design, ‘The Death and Life of Great American Cities.’ This was none other than Jane Jacobs, whose contribution to urbanism is popularly known.

On observing life unfold on the streets and sidewalks, she saw the city as a collection of diverse systems, where individual local characteristics were all interconnected. She propagated the role of higher densities, shorter neighbourhood blocks, local economies and mixed uses, as instrumental in developing a lasting character[6].

William H. Whyte, recording public space [Project for Public Spaces]

“The trust of a city street is formed over time from many, many little public sidewalk contacts. It grows out of people stopping by the bar for a beer, getting advice from the grocer and giving advice to the newsstand man… The sum of such casual, public contact at a local level— most of it fortuitous, most of it associated with errands, all of it metered by the person concerned and not thrust upon him by anyone — is a feeling for the public identity of people, a web of public respect and trust, and a resource in time of personal or neighborhood need.”

-Jane Jacobs

In her opposition of Robert Moses’ plan to build a super-highway through her neighbourhood, she staunchly demonstrated that citizens could hold due rights to their city (‘the right to the city’ became the well-known slogan led by Henri Lefebvre, later revived by David Harvey).

Consideration for the human-scale, for design elements that would contribute to making cities more accessible, usable and relatable, began to take precedence over design dominated by the idea of singular use. The ‘people’ began to take charge of their urban spaces.

This approach to urban planning and design formed much of the basis for the new urbanism movement. ‘Placemaking’ - a tactical, community-centred approach to designing public spaces - grew as a popular tool in the United States, and has been making its way to cities of the Global South.

Placemaking is about arriving at local solutions to local conditions. While it follows a common methodology in different places, it does not force a one-size-fits-all approach, and can therefore be adapted for diverse urban environments. Interventions can be small-scale or large-scale, in city centres or at peripheries, in high-income neighbourhoods or low-income ones – all depending on the available resources and the possible extent of community participation.

For instance, the non-profit Sports Backers’ launched five ‘Jump-Rope Stations’ across the city of Richmond, Virginia. Placed at bus stops and stations, these chest-high pedestals have a jump-rope attached to them which can be used by citizens walking or waiting in the vicinity. Although such an intervention has a small spatial footprint, its impact lies in its method of engaging citizens – it takes ‘play’ in the city from the playground to the streets, and demonstrates the potential of a small object in creating its own place[7].

Left: Jump-Rope Station [Pop-Up City]

In Kiberia, a massive African slum, Kounkuey Design Initiative (KDI) has been planning and implementing a series of long-term projects which connect local assets with existing resources and set up financial, management and leadership systems to empower residents with lasting control. By providing water facilities, institutional infrastructure and reducing flood risks, these projects have positively transformed community places in Kiberia[8].

Left: KPSP-O4 [Kounkuey Design Initiative]

“The city cannot be seen as an isolated and static backdrop for human life, rather an organism connected to the cycles of humanity itself, one which must continuously adapt to include, strengthen and persevere. ”

Aristotle’s notion of synoikismos remains ever valid today, as boundaries between people and identities are constantly being blurred, and the ideals of democracy face unprecedented challenges. Designing sustainable cities[9] is not only about reducing carbon emissions, but about finding solutions to the myriad questions on urban living. These include housing, work, transit, public spaces, economics, informality and much, much more.

The city cannot be seen as an isolated and static backdrop for human life, rather an organism connected to the cycles of humanity itself, one which must continuously adapt to include, strengthen and persevere.

One of the ways in which cities can be re-evaluated are in the strength of its public spaces and its provisions for people’s participation. Placemaking offers a framework for small-scale transformations which can be adapted for local environments, with the potential to impact through cumulative change.

In a developing country like India, which currently contains 5 of the world’s 31 megacities[10], it is imperative to identify the ways in which we can design efficient cities with minimum gaps between citizens, experts, governments and implementing bodies. While keeping theoretical references in mind, it is equally necessary to understand how ‘placemaking’ is relevant to Delhi’s urban environment – one where the urban commons are constantly self-constructed by the movement of people and capital.

We explore Delhi’s public spaces more in our next post.

Stay tuned!

References and Footnotes

1. Democratic Audit UL, ‘Concentrating minds: how the Greeks designed spaces for public debate’, available at <https://www.democraticaudit.com/2016/11/01/concentrating-minds-how-the-greeks-designed-spaces-for-public-debate/>

2. Lineback, N., Gritzner, M.L., ‘Geography in the News: The Growth of Megacities’, National Geographic, available at <https://blog.nationalgeographic.org/2014/02/17/geography-in-the-news-the-growth-of-megacities/>

3. Architectural critic and educator, Paul Goldberger, famously noted that "urbanism works when it creates a journey as desirable as the destination".

4. Silberberg, S, Lorah, K, Disbrow, R, Muessig, A, 2013, ‘Places in the Making: How placemaking builds places and communities’, Department of Urban Studies and Planning, Massachusetts Institute of Technology, Boston, MA, U.S.A.

5. 2010, ‘William H. Whyte’, Placemaking Heroes, Project for Public Spaces, available at <https://www.pps.org/article/wwhyte>

6. 2010, ‘Jane Jacobs’, Placemaking Heroes, Project for Public Spaces, available at <https://www.pps.org/article/jjacobs-2>

7. Philips Pop-Up City, ‘Jump Rope Stations for Playful Public Space’, available at <https://popupcity.net/observations/jump-rope-stations-for-playful-public-space/>

8. Kounkuey Design Initative, ‘The Kiberia Public Space Project’, available at <https://kounkuey.org/projects/kibera_public_space_project_network>

9. United Nations Development Programme, ‘Goal 11: Sustainable cities and communities’, available at <https://www.undp.org/content/undp/en/home/sustainable-development-goals/goal-11-sustainable-cities-and-communities.html>

10. The United Nations defines megacities based on conditions of population (10 million+ people), and urban sprawl.

Torkington, S., 2016, ‘India will have 7 megacities by 2030, says UN’, World Economic Forum, available at < https://www.weforum.org/agenda/2016/10/india-megacities-by-2030-united-nations/>