Planning: Spaces of Migration

Urban planning is conventionally viewed as the practice of a select few - architects, planners and government officials. In India, such groups usually navigate concerns enlisted by numerous urban policies over the years, attempting to strike a balance between our pace of economic growth, the empowerment of local governing bodies as well as the unpopularity of urban centres in the political imaginary (Ahluwalia 2017). Amidst all this, the question of a right to the city can be lost, leaving the lived experiences of cities to the wayside - spaces for leisure, climate oriented designs and most importantly, affordable housing. But a right to the city is more than the imposition of inclusive policy, It's an epistemic position in relation to the lived city, the remembered city - one that requires us to attend to claims to design, space and infrastructure from neglected pockets of urban modernity - the informal settlement or the returning migrant. Instead, we're faced with the prospect of the central vista project, which epitomises the top-down approach by attempting to erase the aesthetic history of New Delhi; imagining space around the capital's democratic institutions to be inaccessible, ahistorical and garishly so. A project of this magnitude in expense and scale bypassed several democratic checks and balances - under some pretence of maintenance, before rapidly felling public criticism in under forty-eight hours. Under such conditions carving out a right to the city wanes in the face of a more vulgar symbolic interest.

My understanding of the urban landscape has been strapped in place by a binary - of models and practice. Planning has teetered between these poles, struggling to find a balance. On the one hand, models that aim at a total, unifying documentation of the urban, struggle with the archive that constitutes its problem. Data that might enable more intensive planning responding to a differentiated population struggles to surface via policy; or leads to dangerously surveillant “smart” bureaucracies. On the other hand, planning, when enacted, is riddled with contingency: variegated users and climates interrupt the program. A practice of modelling the latter, the emergence of practices - is a part of planning that rarely figures into planning critique. As an anthropologist, the built environment has been a neglected dimension of theorisation, albeit a crucial aspect of the description. Perhaps, directing our attention towards the processual character of the built environment - its entanglements with migration, identity and adaptation; might paint the city in terms that stretch beyond conventional models of participation or representation.

Mack’s Construction of Equality

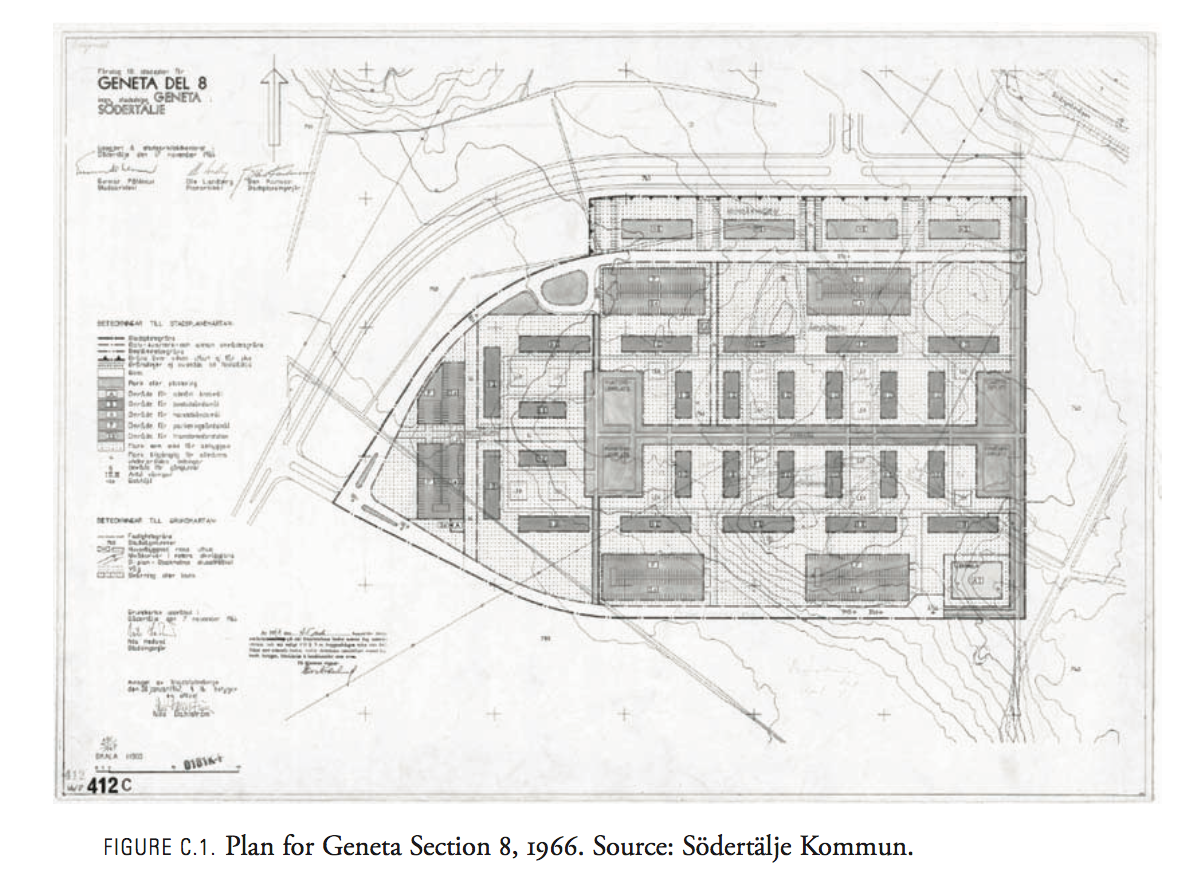

Such symmetrical divisions of the urban, are usually rendered less opaque though the periscope of culture. The Construction of Equality is an ethnography set in a small Swedish city with a population just over 70,000. Written by an anthropologist of architecture, Jennifer Mack, it speaks to cultural cleavages borne of the European migrant crisis and the subterranean xenophobic rage that bubbled and surfaced as a result. Mack’s text begins several decades before, the 1970s, a historical moment characterised by the welfare state. Futuristic projects of housing and design, suffused with a socialist imagination, serve as the architectural site of her ethnographic work. The first chapter recounts the inception of universal housing in the Swedish context, beginning after the second world war. Norms and standards of collective consumption - the hallmark of Ikea furniture - were central to design ethics, through which class differences would be mitigated and a specific citizenry could be forged. The Million Homes Project, which successfully built a million housing units across Sweden, between 1965 and 1974, is the urban manifestation of these aims. Unfortunately, de-industrialisation left these modernist housing projects hollow and under-utilised. But gradually, despite a fledgeling economy, streams of in-migration began to fill these apartments up.

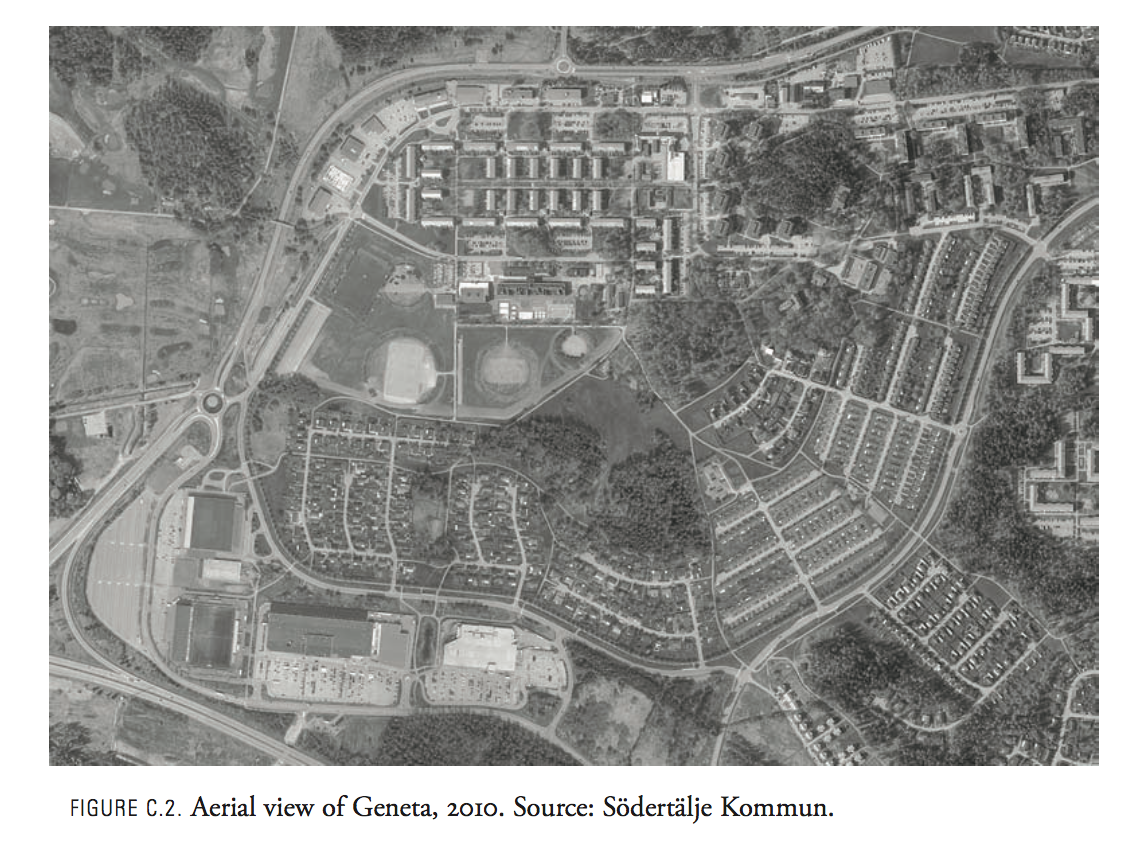

Södertälje, where one such Million Homes project housed immigrants in the 1970s, underwent a series of spatial modifications under pressure from an in-bound Syriac community. Churches, football stadiums and spatially separate enclaves - many of which have been met with sharp criticism (for being “ugly”, “individualistic” and “ostentatious”) from sections of Swedish polity, crop up regularly. It is at these planned intersections that the text begins to investigate certain productive tensions between the lifeworld of Syriac Christians, and the standards and norms that characterise Swedish planning.

Similar tensions exist across various sites in Delhi, despite the absence of affordable housing complexes or durable standards of construction, design or lifestyle. The differences between Delhi and Södertälje are too vast to enumerate. I found it useful to tack Mack’s book as a cue to contemplate how histories of migration into the city could open planners to styles and codes of architecture that negotiate not just various scales, but allow us to imagine land use or design through a toolkit provided by materials and practices mediated by residents themselves. Perhaps then, Mack’s central finding should be seen as a key dimension of planning - to trace out how migration from within India’s heterogeneous bedrock of rural and peri-urban areas, bring a similar proclivity for creativity or adaptation to informal settlements. While many of us would stand by the view, that upgradation and in-situ development remain pervasive and non-negotiable dimensions of planning, my takeaway from this book was its emphasis on migration, cultural desires and their undeniable contributions to a composite mode of planning.

“Urban planning from below” has re-configured Södertälje over several decades, by introducing new built forms via “temporary takeovers of space” that gradually evolved into legitimate modes of design. Instead of a focus on the “user”, “resistance” or “channels of participation”, Mack uses a socio-historical lens to introduce us to the Syriac Standard. Public spaces, designed in the functionalist vein of Södertälje’s architects, tended to revolve around certain activities - squash, public spaces for interaction and gatherings - the centrum. But over time, these have given way to wedding halls, various kinds of retails space and training grounds for two rival football teams, whose games are televised globally. A squash court, constructed in 1974, was intended by professional planners to be a space where residents could “meet [their] fellow humans". Due to neglect and under-usage, the court was shut in 1986, but over two decades the space was converted by the Syriac Community into a wedding hall and has since evolved into a burgeoning business strip.

The intentions of Swedish professional planners failed to factor in how space and culture, invariably remain in dialogue. As a result, Modernism’s appeal to a standard found itself confronted by the world view of new citizens, who sought to carve out their own enclaves. In tracing out the origins of this tendency, Mack works through the public dimensions of Syriac life - one that required their own church for prayer, halls for the various functions that shape their calendar year - many of which found little room to exist in the prescriptions of modernist planning.

The temporality of this method implicates a different mode of place-making that shifts emphasis in planning away from the event of construction - but instead captures planning as a product of social flux generated through increasingly varied architectural forms. Of course, this is contingent on the open character of Södertälje’s governance - design from the bottom up takes place alongside political representation, upward mobility and national debates surrounding the idea of integration. Mack’s interlocutors, members of the Syriac Orthodox community, were all upwardly mobile. Some of them studied at design institutions while the rest were wealthy enough to purchase land close to friends and family - thereby proximate to nodes of power and influence, a citizenry implicated at various stages of design. A neglected element of Mack’s writing then, appears to be the socio-economic context in which such a multicultural cooperation thrived: the universal access to education, housing and work, which shaped the youth of her interlocutors, are all drivers of mobility. It is in the creative pockets of such architectural models that a politics of urbanity invites its residents to test the limits of various political modes.

Södertälje, by inviting immigrants and their cultural value systems into a participative polity, permitted their landscape to change alternative publics. Sweden, more homogenous than Delhi (to stretch this comparison any further would be farcical) - found a sense of harmony disrupted once it’s building standards and architectural aesthetics were modified. Delhi’s own aesthetic “harmony" has been formulated through a middle-class desire, rooted legacies of modernism and an undeniably callous legal edifice - but this hasn’t (and shouldn’t) halt its persisting in-migration and expanding settlements. We might do better to pause and deflect constraints posed by Malthusian metrics, and instead investigate homes and infrastructures that are built every day, especially those that persist under threats of demolition or displacement. In terms that planners and members of civil society in Delhi have engaged with thus far, the Master Plan for Delhi is one of many models, there are numerous others that we fail to translate - those that witness architectures as practice.

Images and photos sourced from Jennifer Mack’s book ‘The Construction of Equality: Syriac Immigration and the Swedish City”